Introduction

Bos taurus and Bos indicus cattle were domesticated independently in Near East and in Indian subcontinent from aurochs subspecies, respectively (Loftus et al., 1994). African cattle breeds were originated in Asia with a large introgression from wild African auroch (Decker et al., 2014). Since their introduction into the content, African cattle have been exposed to a range of new and changing environments and human selective breeding (Hanotte et al., 2010). Due to its geographical proximity to the Horn and East Coast, Ethiopia is served as a genetic corridor for cattle introduction to the continent and center of hybridization (Hanotte et al., 2010). Ethiopia hosts more than 24 diversified cattle populations or strains which are largely composed of indicine genetic background (Rege, 1999, Hanotte et al., 2002, Edea et al.,2015b). These cattle populations show striking variation in terms of morphology, coat colors, and production traits, which may reflect adaptation of the sub-populations to the prevailing diverse local environmental conditions. Cattle populations such as Borana, Begait and Ogaden are adapted to lowaltitude areas with high annual temperatures (12 to 37 °C (23 years of data), low rainfall varying from 594 to 747 mm/years (27 years data), whereas other cattle populations (Arsi, Guraghe, Arado, and Fogera) are mainly distributed mid to high-altitude areas characterized by high rainfall (721 to 1360 mm/year) and relatively low annual temperature (7 to 27°C). On the other hand, over the last few years, Hanwoo cattle have been selected for beef traits, including carcass weight, eye muscle area, backfat thickness, and marbling score (Lee et al., 2014). Specifically, a yearling weight was increased from 315.54 kg to 355.06 kg over the last 13 years (Park et al., 2013). Hence, selection for environmental adaptation and commercial traits may have differently shaped the genome of these cattle breeds.

The availability of genome high-density single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) has facilitated the mapping of signatures selection associated with domestication and selection. Several investigations have been performed to map selection sweeps in cattle (Bahbahani et al., 2017, Bahbahani et al., 2015a, Chan et al., 2010, Makina et al., 2015a). Evidence of positive selection for ecological adaptation has also been investigated in human (Scheinfeldt et al., 2012), sheep and goats (Lv et al., 2014, Kim et al., 2015) and pig (Ai et al., 2013). With the exception of few emerging case studies, the evidence of selection for local adaptation is limited in African cattle population in general and in Ethiopian cattle in particular. Moreover, selection signatures mapping and diversity studies in African cattle or zebu have been mainly performed using Illumina Bovine SNP50K BeadChip (Bahbahani et al., 2015a, Makina et al., 2015b, Edea et al., 2014, Randhawa et al., 2016), which were derived from western commercial cattle breeds. As well demonstrated in our previous studies, taurine origin chips were less informative in African zebu cattle and led to bias estimation of populations parameters compared to the indicine derived SNPs (Edea et al., 2013, Edea et al., 2015a, Edea et al., 2015c). In this study, we used a high density and informative SNPs (80K) specifically developed from Bos indicus breeds to identify divergent selection between Ethiopian and Hanwoo cattle.

Materials and methods

Cattle breeds, SNP genotyping and Quality Control

We sampled 8 Ethiopian cattle populations (n = 245), and taurine reference breed Hanwoo (n = 22). The Ethiopian cattle samples represented 4 traditional breed groups: sanga (Raya-Azebo), zenga (Fogera and Arado), zebu (Begait, Borana, Arsi, Guraghe, and Ogaden). Unelated animals were sampled from multiple herds and villages. Nasal samples were collected using Performagene LIVESTOCK's nasal swab DNA collection kit (DNA Genotek Inc., Kanata, ON, Canada). The Hanwoo (Korean cattle) samples were collected from commercial Hanwoo production farms.

The data that was used for this study is from 128,433 Swine Genetic Improvement Network Program participating breeding farms and 106,410 non participating breeding farms from 248,422 farms that were farm certified by KAIA, Korea Animal Improvement Association, excluding outliers. For the analysis, 5 characters, such as ADG(g), 90KG(day), BF(mm), LMA(㎠) and LP(%) were used.

All animals were genotyped using the 80K Indicine BeadChip (GeneSeek Genomic profiler; GeneSeek, Lincoln, NE, USA) derived mainly from Bos indicus breeds, which comprises 73,794 SNPs. Of 73,794 SNPs, we discarded 3,918 SNPs on the X chromosome, 74 on the Y–chromosome, 13 from mtDNA and 32 unmapped to any chromosome, leaving 69,758 autosomal SNPs mapped to the bovine genome. Autosomal markers were screened for the call rate <90% and minor allele frequency (MAF) <0.05. Additionally, in each population, individuals with a call rate < 90% were discarded. Finally, a total of 67,810 autosomal SNPs for 267 animals retained for the analysis. Quality control measures were performed using SNP and Variation Suite v8.5.0 (Golden Helix, Inc., Bozeman, MT, www.goldenhelix.com).

Detection of selection signals and functional analyses

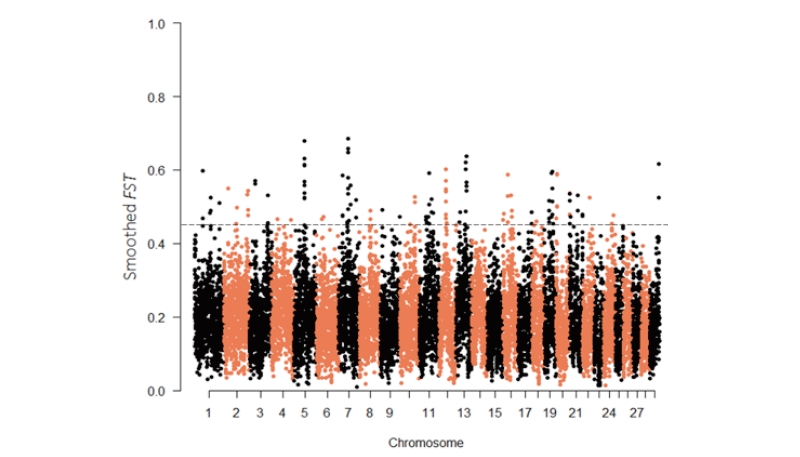

The FST statistics for selection mapping has been widely applied in several studies, including in dog (Akey et al., 2010) and cattle (Ramey et al., 2013, Makina et al., 2015b, Bahbahani et al., 2015a). In order to search for genomic regions that have been under divergent selection in beef (Hanwoo) and Ethiopian cattle populations, genetic differentiation ( FST) was calculated with unbiased estimator proposed by Weir & Cockerham (1984) using SNP and Variation Suite v8.5.0 (Golden Helix, Inc., Bozeman, MT, www. goldenhelix.com). To minimize the specious noise from single SNP based analyses, FST values were calculated with a sliding window of 10 SNPs as used in the previous study (Bahbahani et al., 2015b). As in (Porto-Neto et al., 2013), the most highly differentiated regions representing the top 1% windows of smoothed FST were treated as candidate selection regions. Genes within the specified selection regions were considered as candidate genes.

Results and Discussions

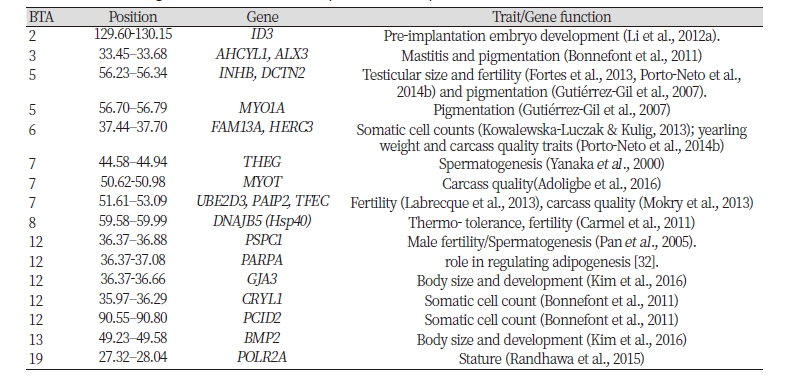

The average genomic FST values averaged in sliding windows of 10 SNPs ( FST –10SNPW) was 0.20 between the Ethiopian cattle and Hanwoo. There are 334 genes within the top 1% windows (135 windows, Tables S1). Some of the regions on BTA7 (52.26–53.09 Mb), BTA12 (35.54–35.94 Mb), BTA13 (57.82–58.13 Mb), and BTA19 (27.32–27.81; 42.78–43.46 Mb) (Table S1) coincide with genomic regions under positive selection in East African shorthorn zebu cattle(Bahbahani et al., 2015a). Within these regions, three candidate genes (EFHA1, ALOX12/ ALOX15, and SLC16A11) concur with the present findings. ALOX15 or ALOX12 is near to QTL for scurs in cattle (Asai et al., 2004). Additionally, the candidate regions on BTA2 (64.62-64.93; 125.29-125.56 Mb), BTA7 (45.73-46.04; 50.62-50.98; 51.61-52.80 Mb), and BTA22 (36.62-37.03Mb) overlap with selection signals identified in West- African cattle breeds (Gautier et al., 2009).

Ethiopian cattle are evolved to adapt to a wide range of stresses (extreme temperature, UV, diseases prevalence, feed scarcity) and natural selection may have left genomic footprints in the underlying genes involved in local adaptation. Interestingly, we detected DNAJB5 (Hsp40) gene on BTA8:59.58-59.99 which is known to be associated with thermo-tolerance (Table 1). Increased expression of Hsp40 is observed in goat during hyperthermic condition (Archana et al., 2017). Further evidence suggests that Hsp40 interact with Hsp70 (Liberek & Georgopoulos, 1993, Schröder et al., 1993). Increased expression of the Hsp40 genes was observed in Drosophila melanogaster subjected to heat-shock (Carmel et al., 2011). In addition to their well-known function of HSPs as molecular chaperones, recent evidence shows that the two heat shock proteins (HSP70 and HSP40) also involved in antiviral immune responses (Dong et al., 2006). A QTL for body temperature has mapped on TA18 (Howard et al., 2014). The candidate gene LOC100299171 overlapped with this region.

The adverse influence of heat stress on reproduction is less pronounced in Bos indicus than in Bos taurus (Paula-Lopes et al., 2013). These differences could be genetic and some of the top 1% windows harbor genes which are involved in embryonic development, or fertility, including ID3, INHBC, UBE2D3, PSPC1, STAT5A, and PAIP2 (Table 1). INHBC is implied as the candidate gene for inhibin (IN) regulation, which is associated with testicular size and fertility in cattle (Fortes et al., 2013, Porto-Neto et al., 2014b). The gene ID3 plays a vital role in the regulation of pre-implantation embryo development (Li et al., 2012a). Gene expression studies in high and low fertility heifers have revealed that UBE2D3 is linked to fertility (Killeen et al., 2014). PAIP2 was detected as under selection and associated with the reproductive traits in goats (Guan et al., 2016). PSPC1 is abundantly expressed in the mouse testis and implicated in regulating nuclear events during spermatogenesis (Myojin et al., 2004). STAT5A contains QTL for early embryonic survival (Khatib et al., 2008), associated with fertilization rate (Khatib et al., 2009), and sire conception rate (Li et al., 2012b).

Ethiopian cattle populations are better survived and produce under high diseases and parasites loads. Four of the candidate genes (AHCYL1, FAM13A, HERC3, PCID2, and CRYL1) (Table 1) are related to the mastitis and somatic cell count in dairy breeds. In their study (Bonnefont et al., 2011) demonstrated that AHCYL1, PCID2, and CRYL1 genes were differentially expressed between mastitis resistant and susceptible lines of dairy sheep. Similarly, variation within in the FAM13A gene was reported to be related to increased levels of somatic cell counts in Jersey cattle (Kowalewska-Luczak & Kulig, 2013).

Ethiopian cattle population show striking variation in terms of coat color, whereas Hanwoo cattle predominantly display brown coat color(Choi et al., 2012). Accordingly, we detected genes related to coat color phenotypes (ALX3, DCTN2, and MYO1A (Table 1)). It has been shown that Alx3-mediated repression of Mitf in rodents (Mallarino et al., 2016). MITF is a master regulator of melanocyte differentiation (Hou & Pavan, 2008) and known to influence white spotting patterns in cattle (Qanbari et al., 2014), swap buffalo (Yusnizar et al., 2015), horses (Hauswirth et al., 2012), and dogs (Rothschild et al., 2006). Additionally, the candidate region on BTA6 (37.44–37.70 Mb) overlaps with QTL for the degree of spotting in cattle (Reinsch et al., 1999). MYO1A and DCTN2 are reported to have an influence on pigmentation in Charolais × Holstein population (Gutiérrez-Gil et al., 2007). The regions on BTA5 (56.59-56.70 Mb) and BTA6 (29.72–30.03 Mb) contain QTLs for coat color and coat texture (Liu et al., 2009, Mészáros et al., 2015, Huson et al., 2014). Given the importance of coat color and texture in thermoregulation (Gebremedhin &Wu, 2001); these genes are potential candidates for zebu adaptation to hot tropical areas.

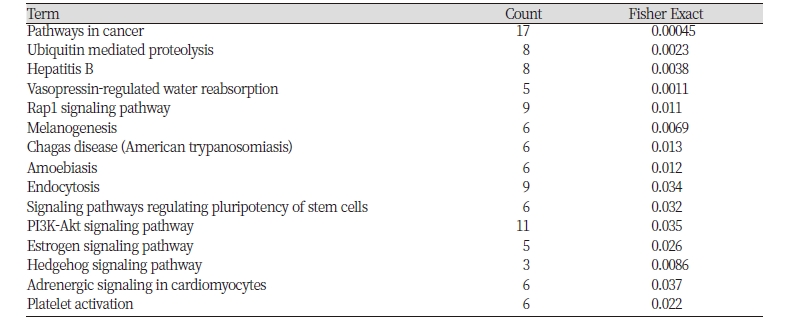

Our gene functional enrichment analysis revealed important pathways that may be involve in African cattle adaptation under tropical hot environments, including “vasopressin-regulated water reabsorption” (P = 0.001), “Rap1 signaling” (P = 0.011), “PI3K-Akt signaling” (P = 0.035), and “melanogenesis” (P = 0.007, Table 2). Water reabsorption is one of the physiological mechanisms for animal adaptation under dry habitats (CAIN III et al., 2006). A recent study involving Chinese sheep breeds evolved under arid environments detected highly enriched biological pathways for water reabsorption (Yang et al., 2016). In cattle, heat stress increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation at 40 °C (Singh et al., 2014). Generation of ROS is a response to stress conditions (Pastori & Foyer, 2002). The Rap1 signal was involved in the suppression of Ras-generated reactive oxygen species and protection against oxidative stress (Remans et al., 2004). The PI3K signaling pathway plays an important role in Hsp90 chaperone functionthrough regulating the expression of heat shock protein (Hsp70) (Chatterjee et al., 2013, Tu et al., 2000). Thus, these pathways are likely relevant for Ethiopian cattle adaptation under stressful environments

Compared with Ethiopian cattle populations which are characterized by a short stature, and low productivity, Hanwoo cattle have undergone selection for yearling weight and beef quality traits, including carcass weight, eye muscle area, and backfat thickness (Lee et al., 2012, Flori et al., 2009). Intriguingly, we detected some candidate genes (TFEC, HERC3, POLR2A, BMP2, GJA3, PARP4, and MYOT) (Table 1) within the top 1% windows related to stature, body size, and beef quality traits. TFEC and HERC3 are associated with a backfat thickness and yearling weight in beef cattle, respectively (Mokry et al., 2013, Porto-Neto et al., 2014a). Polymerase (RNA) II (DNA directed) polypeptide A (POLR2A) contains functional variants contributing to the genetic control of bovine stature (Randhawa et al., 2015). BMP2 and GJA3 are well-known genes for body size and development (Fan et al., 2011) and undergone selection in sheep and goat breeds adapted to hot arid environments (Kim et al., 2016). More importantly, the GJA3 gene is identified as under recent selection in brown Hanwoo cattle (Lim et al., 2016). Genetic variation within the PARP4 has found to be associated with carcass weight in commercial Hanwoo cattle (Edea et al., 2018) and regulates adipogenesis. MYOT is involved in myofibril assembly and actin binding in the muscle tissue (Schessl et al., 2014). Recent functional analysis revealed the association of mutations within MYOT with loin muscle area, backfat thickness and intramuscular fat in cattle (Adoligbe et al., 2016).

In conclusion, by comparing cattle breeds with distinct evolutionary and breeding legacies, we identified candidate genes under directional selection and pathways which may contribute to further understanding of the consequence of natural and/or artificial selection in shaping the diversity of modern cattle breeds.