Introduction

The copy number variations of immune genes may play an important role to improve animal fitness and their survival (Wang et al. 2016; Wurschum et al. 2017; Zhang et al. 2019; Li et al. 2020). The difference in the copy number of immune genes among difference species may have been resulted from biological needs of each species during their evolution (Hollox and Abujaber 2017; Minias et al. 2019). Intraspecies differences in the copy number differences or lacking a specific immune gene influence the immune capacity of animals (Qutob et al. 2009; Siddle et al. 2010; Wong et al. 2022). Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) are found in various species including plants, insects, and vertebrates and serves as a first line defense system that exhibits a broad and antimicrobial reactions against pathogens (Izadpanah and Gallo 2005; Bahar and Ren 2013).

Several families of AMPs have been found including defensins, cathelicidins, dermcidin, hepcidin, NK-lysin and granulysin (Ganz et al. 1985; Andersson et al. 1995; Pena and Krensky 1997; Park et al. 2001b; Schittek et al. 2001b; Zanetti 2005). Interestingly, the number of AMP family genes among mammalian species varies, and the difference was clear especially for cathelicidins and defensins (Zanetti 2005; Choi et al. 2012; Kang et al. 2020). In this review, we tried to summarize the current understanding on the evolution and species variations of β-defensin genes among different mammalian species. This review provides a basis to understand the changes of AMP genes and genetic structures in livestock animals during their evolution.

Antimicrobial peptide and innate immunity

AMPs are diverse peptides with broad spectrum antimicrobial activities against bacteria, fungi, and viruses and are a part of the innate immune system (Hwang and Vogel 1998; Lai and Gallo 2009). Most endogenous AMPs are positively charged small peptides with hydrophobic residues comprising approximately 12–50 amino acids (Lai and Gallo 2009; Kim et al. 2017). They are widely distributed throughout the plant and animal kingdoms (Zasloff 2002), and are also being considered as potential candidates for pharmaceutical applications (Kang et al. 2012; Seo et al. 2012).

The broad antimicrobial activity of AMP is manifested by their ability to form pores on the surface of pathogenic substances (Yeaman and Yount 2003). The mechanistic models for the pore formation by AMPs have been described (Nguyen et al. 2011), but the mechanisms may vary among AMPs, and the precise mechanism is less clear. However, most AMPs have cationic charges and amphipathic structures with hydrophobic residues (Nguyen et al. 2011). The cationic nature of AMPs is thought to interact with negatively charged membranes of pathogenic organisms. However, some AMPs are known to exhibit antimicrobial activity through mechanisms that inhibit DNA or protein synthesis rather than cell membranes (Brogden 2005; Nicolas 2009). In accordance with the characteristics of AMP which exhibits activity through various mechanisms, AMP forms various protein structures including α-helical, β-stranded, β-hairpin, loop, and extended structure which are different from the others. Advances in nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) technology has revealed some of the details of AMP structures (Hwang and Vogel 1998).

Although it is difficult to clearly classify all AMPs according to a specific type due to the structure of AMPs, AMPs are classified into several classes according to their structure (Table 1). The largest group of α-helical AMPs is α-helical cathelicidin. Cathelicidin has a highly conserved sequence in the N-terminal, a cathelin like domain, and a highly diverse C-terminal antimicrobial domain. These highly variable regions form various structures of cathelicidin. As a result, cathelicidin has many other forms besides α-helical structure (Kościuczuk et al. 2012). Another α-helical structure AMPs include NK-lysin and granulysin. Those peptides are consisted with five compact α-helical segments. NK-lysin and granulysin are found in pig and human lymphocytes and are known to be employed by by cytotoxic lymphocytes to kill pathogens (Andreu et al. 1999). Another main group of AMPs is defensins. These group of AMPs are characterized by abundant cysteines and disulfide bonds connecting them (Ganz 2003).

Defensins are found from various species including plants, insects and all vertebrates (Ganz 2004). Hepcidin and LEAP-2 are also AMPs rich in cysteine. Hepcidin and LEAP-2, in which eight cysteines are linked by disulfide bonds, are known as AMPs expressed in the liver (Park et al. 2001a; Krause et al. 2003). Dermcidin, an AMP produced by the glands and secreted with sweat, was first discovered in humans and has no homology with any other AMP (Schittek et al. 2001a). The secondary structure of dermcidin analyzed by circular dichroism spectroscopy indicated that the structure of dermcidin is variable and seems to have both α-helix and β-sheet structure (Lai et al. 2005). Different types of AMPs depending on peptide structure and function allow to cope with various pathogenic agents, which serve as a part of important nonspecific immune substances.

Defensins – the biggest group of antimicrobial peptides

Among the classification according to the structure of AMP, defensins belonging to β-sheet AMP and are one of the largest family of antimicrobial peptide family. Defensins are widely expressed in mammalian epithelium and phagocytes and is known to help antimicrobial activity of phagocytes or to be secreted by epithelial cells (Ganz 2004). Defensins have six cysteine motifs that are conserved among different species and are classified into α-defensins and β-defensins depending on the binding pattern and placement of these cysteines.

The α-defensin has disulfide bonds in 1-6, 2-4, 3-5 cysteines and β-defensin, on the other hand, has disulfide bonds in 1-5, 2-5, 3-6 cysteines (Ganz 2003). Recently, θ-defensin, a defensin subfamily found in primates, has been discovered and is known to be very structurally different from existing defensins such as having a cyclic form (Tang et al. 1999). Interestingly, the defensin family is evolutionarily well conserved, such as forming identical clustering in vertebrate lineages or having similar peptide precursors, suggesting that vertebrate defensins may be evolved from common genes of identical origin (Hughes 1999). In particular, various studies have shown that the β-defensin family, the largest of the vertebrate defensin family, is formed by repetitive duplication events (Hughes and Yeager 1997). As a result, the β-defensin gene appears to form constant clusters in vertebrate lineages, and the number of β-defensin clusters and β-defensin genes was relatively high in the more recently evolved species. For example, a chicken phylogenetically distant to mammals has a single defensin cluster and 13 β-defensin genes (Xiao et al. 2004), but opossums have three defensin clusters and 37 β-defensin genes (Belov et al. 2007).

In humans, defensins diverged in the relatively recent time period and has 5 defensin clusters and 43 genes (Patil et al. 2005). A more interesting fact about the evolution of β-defensin is that peptides with similar structures to β-defensin in vertebrates are found in non-vertebral lineages. Big defensin, an AMP found in horseshoe crab, mussels and amphioxus, has a β-sheet structure and disulfide bonds similar to that of vertebrate β-defensin and the gene positions encoding these have been evolutionarily conserved as a single exon upstream of the phase I intron. Also, similarly with β-defensin, when comparing big defensin of Protostome (mussels are included) and Deuterostomes (amphioxus are included), the big defensin are found to be monophyletic (Zhu and Gao 2013). These findings suggest that the origin of β-defensin in vertebrates may have appeared relatively early enough to be associated with the evolution time period of some invertebrates. Interestingly, plants and insects also have defensin genes with cysteine motifs, which appear to originate from the bacterial defensin-like peptide (Gao et al. 2009). However, the evolutionary relationship between those defensins and big defensin and vertebrate β-defensin is still vague. But evolutionary facts about β-defensin show that these AMP genes are closely related to vertebrate evolution.

Genome duplication as a main cause of β-defensin gene amplification

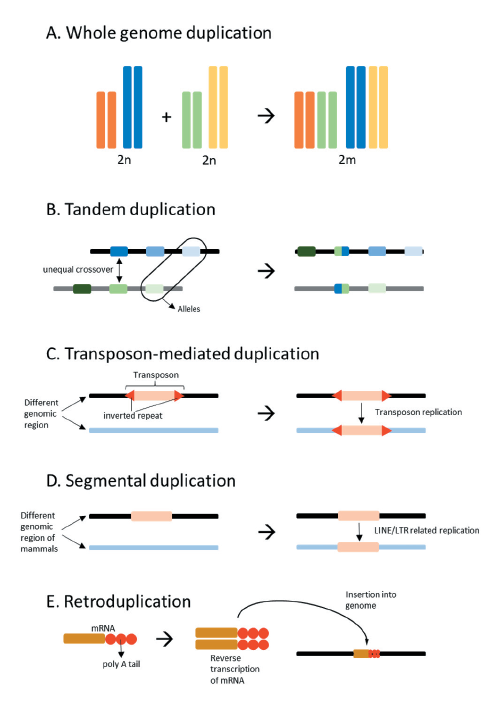

Gene and genome duplication is an important factor in gene evolution by generating additional copy of the gene and provides a new source for evolution while maintaining the function of existing genes (Ohno 1974; Holland 2003). Gene duplications can occur by chromosomal nondisjunction and tandem duplication caused by unequal crossing over, transposon-mediated duplication by transposable element, segmental duplication, and retroduplication forming duplicated sequences by insertion of reverse-transcribed DNA (Figure 1). Especially, segmental duplication forms long repeats of 1 to 200 kb, offers a structure that is very suitable target for homologous recombination (Samonte and Eichler 2002).

Fig. 1. Types and mechanisms of gene duplication. Whole genome duplication due to ploidy (A). Tandem duplication formed by unequal crossover of similar sequences (B). Transposon-mediated duplication formed by mutator-like elements (MULEs) (C). Segmental duplication formed by long interspersed nuclear elements (LINE) and long terminal repeat retroposons (LTR) in mammals (D). Retroduplication formed by insertion of a retrogene which is a reverse transcript of mRNA (E).

Very few of the highly replicated sequences formed by duplication are transcribed and translated to have specific functions, and in the most cases they exist as pseudogenes. However, a duplicated pseudogene may remain neutrally selected by its functional pair gene (Zhang 2003). In addition, the duplicated genes with functions remain free from purifying selection and form a gene family composed of paralogous genes (Zhang 2003).

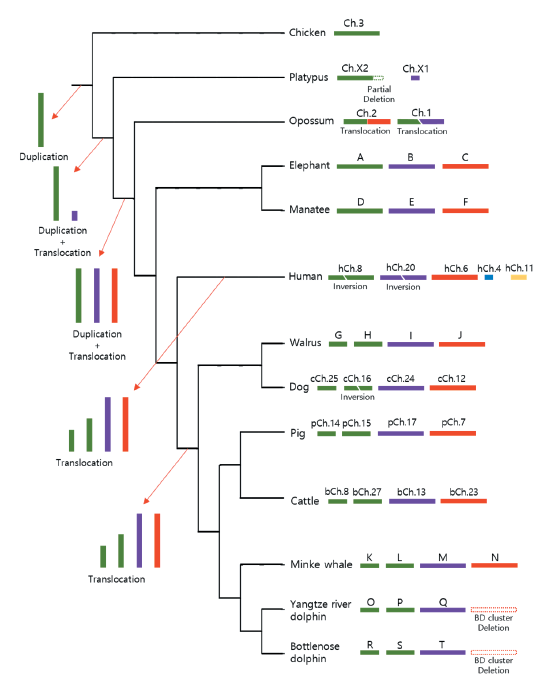

Gene families have very different family sizes depending on the composition of the paralogous genes and the species. For example, in case of Drosophila, the trypsin gene family is the largest gene family (Gu et al. 2002), while in mammals the olfactory receptor gene family is the largest (Zhang and Firestein 2002). However, the size of the gene family and the proportion of functional genes present in the gene family are not directly proportional and vary widely between species. In humans, more than 60% of the olfactory receptor family is a pseudogene, whereas in mice only 20% (Rouquier et al. 2000). This is thought to be the result of natural selection because of the greater dependence on the olfactory sense in mice than that of humans. Gene duplication is thus an important evolutionary trigger that leads to the emergence of new genes to enter natural competition. The association of genome duplication with the duplication of β-defensin genes was described recently (Figure 2).

Fig. 2. A diagram showing the expansion of β-defensin (BD) clusters in mammals. The tree indicates the order of speciation from the mammalian ancestors without considering genetic distances. Chicken (Gallus gallus ) was used as an out-group. ΒD clusters of the same syntenic origins are indicated with the same color. Therefore, the BD clusters in green are of the ancestral cluster. The expansion of BD clusters is indicated by arrows at the tree branch. Arrangements of BD clusters for each species are shown next to species names together with names of chromosomes or letters in the case of scaffolds. Deletions of BD cluster are indicated for Odontoceti species (Yangtze river dolphin (Lipotes vexillifer ) and bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus )). The accession numbers for each scaffold are NW_003573442.1 (A), NW_003573439.1 (B), NW_003573420.1 (C), NW_004444027.1 (D), NW_004443944.1 (E), NW_004444151.1 (F), NW_004450303.1 (G), NW_004450527.1 (H), NW_004450277.1 (I), NW_004452022.1, NW_004451088.1 (J), NW_006731901.1 (K), NW_006729679.1 (L), NW_006732234.1 (M), NW_006732678.1 (N), NW_006798803.1 (O), NW_006773710.1 (P), NW_006771517.1 (Q), NW_017842997.1 (R), NW_017844527.1 (S), and NW_017844299.1 (T).

Underwater re-adaptation of marine mammals

In late Devonian, first terrestrial vertebrates were evolved from marine sarcopterygian fish. Since this evolutionary event, all vertebrates in terrene time periods were formed (Carroll 2001). Since the appearance of terrestrial vertebrates, some of their descendants had left their land environment and adapted to aquatic environments again. Based on fossil data, placodonts, turtles, penguins, sirenians, and pinnipeds were adapted to aquatic environments from approximately 245, 220, 62, 49, and 28 Mya, respectively (Uhen 2010a). The oldest Cetacean lineage fossil for mammalian lineage was found 52.5 Mya, early Eocene (Bajpai and Gingerich 1998).

There are three major families of aquatic mammals: Cetacea, Sirenia, and Pinnipedia. Cetaceans include whales and dolphins and sirenians include dugongs and manatees, and they have fully adapted to aquatic environment. In contrast, pinnipeds including seals and walruses dwell both aquatic and land environment (Domning 2018a). Cetaceans are subdivided into two sublineages, Mysticeti and Odontoceti which contain whales and dolphins respectively. Recent molecular biological analyses using DNA sequences have shown that Cetaceans are closely related with Artiodactyla, including cattle, sheep and pigs, with the nearest land sister taxa, Hippopotamidae which includes hippopotamus (Nikaido et al. 1999; Gatesy and O'Leary 2001).

Another interesting point is that river dolphins, a subgroup of Odontoceti, are morphologically and phylogenetically different with marine dolphins and adapts to freshwater rather than sea water (Hamilton et al. 2001). Molecular genetic studies based on mitochondrial gene and fossil records of river dolphins have shown that they had spread throughout the whole globe in middle Miocene, when sea levels were high. However, when the sea level lowered and the ocean changed to freshwater during late Neogene, the river dolphins were thought to have evolved and adapted to the area (Hamilton et al. 2001).

Sirenia is the only herbivore marine mammal lineage which has a complete marine lifeform. According to the fossil record, Sirenia existed on Earth from about 50 Mya, late early Eocene. Only four species (1 Dugong and 3 Trichechus) survive today, and sirenians are the closest species to elephants in Proboscidea. Sirenia and Proboscidea genera form Tethytheria. The main habitat of sirenians is shallow seas and river coasts around the world (Domning 2018b).

Pinnipedia, another independent aquatic mammal lineage, comprise fur seals and sea lions (otariids), walruses(odobenid), seals(phocids). According to the fossil record, their appearance was 27-25 Mya, late Oligocene. Recent molecular biological information indicate that Pinnipeds are a monophyletic group, and their closest modern family is Ursidae which bears are included. It is believed that early pinnipeds were coastal predators that ate small fish according to the maxilla fossil of Pteronarctos, the ancestor of pinnipeds (Berta 2018).

Convergent evolution of aquatic mammals

Despite three independent evolutionary events in aquatic mammalian lineages, several convergent evolutionary characters are found in aquatic mammals, such as streamlined body, hind limb degeneration, and loss of sweat and eccrine glands (Foote et al. 2015; Huelsmann et al. 2019). Various studies have now identified and explained the function of positively or negatively selected genes in aquatic mammals comparing to terrestrial mammals. As a result, many genes appear to be involved in the adaptation of marine mammals to the aquatic environment. For examples, S100A9 and MGP genes, which encode calcium binding proteins, were found to be positively selected to alter the amino acid sequences in aquatic mammals unlike in terrestrial mammals (Foote et al. 2015). As a result, they could evolve to have bone density appropriate for their aquatic habitat convergently.

However, despite a variety of studies, information on immune-related genes which are directly associated with individual survival of aquatic mammals are still limited (Shen et al. 2012; de Sá et al. 2019). Enormous environmental change in adaptation from land to sea would have resulted in a very strong selection pressure on the genes involved in the organism's biological defense system. The ability of the innate immune system to primarily block the invasion of pathogenic substances by using physical and physiological methods would be very important for the survival of species. The changes of antimicrobial peptide (AMP) gene families in the aquatic mammals would be interesting and meaningful to understand the changes of immune systems according to the environmental changes.

Duplication and contraction of β-defensin gene family in Odontoceti due to habitat change

The independent terrestrial to aquatic habitat changes in different lineages of marine mammals including sirenians, pinnipeds, and cetaceans indicate that the common ancestors of each lineage had to adapt to entirely new environments (Uhen 2010b). As these marine lineages gradually adapted to the aquatic environment, there was a potential loss of genes that are not required for adaptation to the new environment (Hecker et al. 2017; Sharma et al. 2018; Huelsmann et al. 2019; Liu et al. 2019). Among the genes that undergo more relaxed selection in response to reduced environmental selection pressure, the genes showing the most significant gene loss are the olfactory receptor genes. The olfactory receptor gene family which consists of more than hundreds of genes across the entire chromosome has been extensively contracted in each lineage of marine mammals especially in cetaceans which were fully adapted to aquatic habitat and showed a dramatic change in OR gene repertoire (McGowen et al. 2008; Zhou et al. 2013; Feng et al. 2014). This rapid contraction of the gene family was also found in the β-defensin gene families consisting of the largest gene family among antibacterial peptide genes (Kang et al. 2020).

Like the OR gene, the decrease in the number of β-defensin genes was remarkable in cetaceans and the complete loss of orthologous β-defensin block 1 was observed in most species classified as toothed whale (Odontoceti) (Figure 3, (Kang et al. 2020)). The only Odontoceti species having functional β-defensin genes in BD block 1 was the sperm whale (Physeter catodon), and thus the contraction of β-defensin block 1 in Odontoceti is thought to have occurred after the sperm whale evolutionarily diverged from other toothed whale suborders because the sperm whale shared the most common ancestor earlier with the other Odontoceti species (Kang et al. 2020).

The contraction of the gene families in response to habitat changes provides important insights into how species adapted genetically to their environments. Gene contraction emerged as a result of relaxed selection to a varied environment, but this reduction may improve the fitness of the species in adapting to the new environment. For example, the AMPD3 gene which encodes an erythrocyte-specific enzyme that increases erythrocyte ATP levels is lost in sperm whales because ATP serves as an allosteric effector that stabilizes O2-unloaded hemoglobin in vertebrates and the loss of AMPD3 results in a reduced O2 affinity of hemoglobin (O'Brien et al. 2015). This loss lowers the affinity for O2 in hemoglobin, allowing a smoother supply of oxygen to oxygen-poor tissue. As a result, sperm whales evolved to be able to dive into very deep water and survive without suffocation.

Another example is the loss of SLC22A12, SLC2A9, and SLC22A6 genes in fruit bats. There is a study showing that loss of these genes reduces urine osmolality in experiments using KO mice (Eraly et al. 2008; Preitner et al. 2009). These gene losses cause fruit bats to excrete very dilute urine. This change helps to preserve electrolytes in fruit bats because the conservation of electrolytes is very important due to the ecological characteristics of fruit bats which feed on juicy fruits (Sharma et al. 2018). As seen in sperm whales and fruit bats, the loss of gene function caused by relaxed selection can facilitate important changes to adapt to a new environment, and accordingly, the loss of β-defensin blocks in Odontoceti may be an important adaptive consequence for these species to adapt to the marine environment.

Challenges and limitations

Although genome information of diverse animal species is currently available, their assembly levels are not chromosome level, and accuracy often need further improvements except several species extensively studies. Such limitation serves as a bottleneck for the identification of orthologs for the gene families of interest. Therefore, the availability of genome assemblies with high accuracy for various mammalian species inhabiting diverse environments should provide more insights into the interesting questions on the adaptive genetic changes to environmental changes. Especially, comparative analysis on reproduction and immune related genes would be interesting for mammals. The results should contribute to illuminating the influence of diverse evolutionary dynamics occurring for the genetic adaptation to environmental changes.

Conclusion

Gene duplication is a major mechanism to form a new gene group and a major driving force involved in the generation of gene clusters, functional changes of genes, and even speciation. There is evidence that the gene group consisting of multiple clusters evolved according to repeated duplications following birth-and-death model of evolution. The mechanism also influenced the formation of the β-defensin gene family which constitutes the largest gene family among the antimicrobial peptide genes. In this review, we summarized the results of previous research on the duplication and contraction of the AMP gene family in mammals especially focusing on animals adjusted to the marine environment including sirenians, pinnipeds, and cetaceans. The relaxed selection of pathogenic bacteria in the marine environment may trigger the contraction of AMP family genes such as defensins comparing to their terrestrial relatives such as artiodactyls. However, it is still unclear how this gene loss in cetacean lineages is related to their adaptation to the habitat change. Further studies on genetic changes according to environmental adjustment will be interesting. This review provides current understanding on the adaptive changes of AMP repertoire according to environmental changes.