1Department of Animal Breeding and Physiology, College of Animal Science, Joseph Sarwuan Tarka University, Makurdi, Nigeria

2Department of Veterinary Science, Mattu University, Mattu, Ethiopia

3School of Animal and Range Sciences, Hawassa University, Hawassa, Ethiopia

Correspondence to Chiemela Peter Nwogwugwu, E-mail: chiemelapeters@gmail.com

Volume 9, Number 3, Pages 105-113, September 2025.

Journal of Animal Breeding and Genomics 2025, 9(3), 105-113. https://doi.org/10.12972/jabng.2025.9.3.1

Received on March 27, 2025, Revised on August 22, 2025, Accepted on August 27, 2025, Published on September 30, 2025.

Copyright © 2025 Korean Society of Animal Breeding and Genetics.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0).

The selection of replacement strategies for bulls and heifers in beef cattle populations is a pivotal aspect of livestock breeding programs, impacting genetic improvement and production outcomes. Despite its importance, there remains a dearth of comprehensive studies evaluating the influence of sex replacement strategies on the accuracy of estimated breeding values (EBVs). In this simulation study, various scenarios of male to female replacement ratios were explored using QMSim software to generate datasets representative of beef cattle populations. Our findings highlight the significance of balanced sex replacement strategies, with the scenario featuring a ratio of 40 males to 80 females (40M:80F) consistently demonstrating superior accuracy of EBVs across multiple generations compared to other scenarios. This enhanced accuracy is attributed to the maintenance of genetic diversity and effective mating strategies facilitated by a larger pool of breeding pairs. Conversely, scenarios with imbalanced sex ratios, such as 20M:40F, exhibited reduced accuracy due to limited genetic diversity and potential inbreeding effects. The enduring superiority of the 40M:80F scenario underscores its efficacy in providing reliable breeding value estimates and highlights the need for careful consideration of sex replacement strategies in optimizing genetic improvement programs. These findings contribute valuable insights to livestock breeding practices and emphasize the importance of adopting nuanced approaches to sex replacement strategies for sustainable genetic enhancement in beef cattle populations.

Accuracy of estimated breeding value, livestock breeding, sex replacement strategies, simulation study

The replacement strategy for bulls or heifers is not fixed but rather depends on the breeding objective and production system. The decision to choose a replacement strategy, whether it be a bull or a heifer, should be based on several factors including herd size, existing cow base, farm facilities, ability to source replacements, and implications for cash flow (Aidan, 2015). According to Van Eenennaam & Bullock (2015), the genetic gain is primarily controlled by sire selection. Therefore, when deciding to improve production or reproduction traits, it is crucial to consider this scenario. Although it may seem logical to focus on female selection to enhance fertility, bulls are the main focus for selection. This implies that sires produce a higher number of progeny each year compared to dams, which typically have only one calf per year. The authors also underscored the economic significance of reproduction and put forth the notion that cow-calf producers who are rearing their replacement heifers should also pay heed to the selection of maternal traits. Nevertheless, a majority of the commercial producers lack any documentation of expected progeny differences or estimated breeding values (EBV) upon which to base their decisions regarding replacement selection.

Estimated breeding values (EBVs) of chosen individuals are commonly used to enhance the genetics of economically important traits in livestock species. These values incorporate the outcomes of assessments using pedigree records and phenotypic performance of individuals with the best linear unbiased prediction (BLUP) method (Henderson, 1975; Xu-Qing et al., 2008; Hayes et al., 2008). The accuracy of EBV plays a crucial role in influencing the accuracy of selecting breeding animals (Van der Werf, 2015). Consequently, the choice of replacement strategies may depend on the utilization of reliable records and the availability of data during the selection process. This includes pedigree data, phenotypic performances, EBVs, test accuracy related to the selection objective, and the rate at which replacement occurs. Specifically, the rate of replacement focuses on the proportion of males or females selected to be reintroduced into the herd annually. If the EBVs of the replacement females’ sires are known, then half of their genetic value is also estimated (Van Eenennaam & Bullock, 2015). Various replacement strategies have been employed in diverse breeding and production systems; however, no information was found that compared the effect of sex replacement strategies on the accuracy of EBVs in beef cattle populations across generations.

In addition, recent trends in advanced beef production systems particularly in developed countries highlight artificial insemination (AI) as the dominant breeding strategy, often relying on a few highly proven bulls. This approach enhances the rate of genetic gain but may introduce challenges such as reduced genetic diversity. Conversely, in many developing countries where natural service remains the predominant practice, the dynamics of replacement strategies differ, and the implications for genetic progress are less understood.

Simulation research enables the examination of multiple hypotheses, facilitating an elucidation of the intricate patterns of evolution that would otherwise be challenging to comprehend. For instance, the study of human migration history offers valuable insights into the existing patterns of DNA variation among humans (Rogers et al., 2007; Marchani et al., 2007; Carvajal- Rodríguez, 2008), as well as the comparison of various evolutionary theories (Schaffner et al., 2005; Peng & Kimmel, 2007). In the context of livestock, simulation studies have yielded valuable information regarding the potential of beef cattle and other species for genomic evaluation. These studies have also been employed to investigate the prediction of total genetic value (Meuwissen et al., 2001), genomic prediction of simulated multi-breed and purebred cattle (Kizilkaya et al., 2013), the accuracy of genomic selection in simulated populations (Brito et al., 2011), a comparison between single- and twostep GBLUP methods in simulated beef cattle (Piccoli et al., 2018), and the assessment of genomic prediction accuracy using different selection and evaluation approaches in a simulated Korean beef cattle population (Nwogwugwu et al., 2020). While these studies provide important insights into genomic evaluation, there is still limited evidence on how different sex replacement strategies, under both natural service and AIoriented systems, affect the accuracy of EBVs across generations.

In this simulation, we delve into the crucial realm of beef cattle population dynamics, specifically examining the impact of sex replacement strategies on the accuracy of EBVs. Unravelling the intricacies of these strategies is paramount for enhancing our understanding of genetic contributions to the accuracy of breeding values within the population, and optimizing the sex replacement strategy based on the accuracy of EBVs across scenarios. It is expected that using simulated data, clearer and deeper understanding of these strategies can be attained.

This study was conducted in strict accordance with ethical standards and guidelines. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB), Joseph Sarwuan Tarka University, Makurdi, Benue State, Nigeria. The ethical approval reference number for this study is JSTU/IRB/2024/09 and all computational procedures were adhered.

In this study, the data simulated on the phenotypes was generated using the QMSim software (Sargolzaei & Schenkel, 2009) in order to replicate the real structure and degree of linkage disequilibrium (LD) that is present in beef cattle (Brito et al., 2011). The population structure and parameters of the simulation process are summarized in Table 1. Initially, a historical population (HP) was simulated, consisting of a constant number of 1,000 individuals across 1,000 generations. Subsequently, the population size gradually decreased to 200 individuals (100 males and 100 females) over the next 95 generations, to establish an initial state of LD and mutation-drift equilibrium. Moreover, the HP was formed through random mating. Following this, 200 individuals (effective population size, Ne) were randomly chosen from the last generation of the historical population to expand the population size. All males and females were randomly paired for mating avoiding close relatives to maintain genetic diversity. A minimum kinship threshold was imposed to prevent inbreeding, reflecting real-world cattle management practices. Each female produces five offspring per generation for a total of 20 generations.

Table 1. Population structure and simulation parameters

테이블

Finally, 200 males and 2000 females were randomly selected from the expanded population. These selected individuals were simulated over ten recent generations, with each dam producing one offspring. This process was carried out using six different replacement ratios, as shown in Table 2. Six different replacement rate scenarios were tested, selected based on their relevance to practical beef cattle management. These included combinations of male and female replacements to determine their impact on genetic evaluation. The chosen replacement rates (10%, 20%, 30%, 40%, 50%, 60%) reflect typical industry practices and variations in beef cattle herd management. The accuracy of estimated breeding values (EBVs) for various scenarios were compared over a few generations. Each scenario was replicated 20 times to ensure that the results are statistically robust and not due to chance. The rate of missing sire and dam records was 0.05. Phenotypic values were generated using the equation: where represents the residual error, assumed to follow a normal distribution. True breeding values (TBVs) were generated using a genetic architecture that follows a polygenic model with a heritability of 0.40, consistent with previous studies on carcass traits (Smith et al., 1976; Johnson et al., 2024) and phenotypic variance of 1.

Table 2. Replacement strategies used in different breeding and production systems

테이블

The Henderson mixed linear model was employed to predict the EBVs, while the accuracy of the EBVs was calculated using Pearson’s correlation. The R version 4.2.0 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) was incorporated in the analyses. The model below was used to compute traditional BLUP using BLUP90 software (Misztal et al., 2014)

BLUP procedure: the pedigree data and phenotypes were used for estimation.

수식

where y, b, a and e are the vectors of the phenotype, overall mean, additive genetic effect and residual errors, respectively, X and Z are coefficient matrices.

The accuracy of EBVs was calculated as the Pearson correlation between EBVs and TBVs across generations. The effect of reduced accuracy on selection intensity and subsequent genetic gain was not evaluated

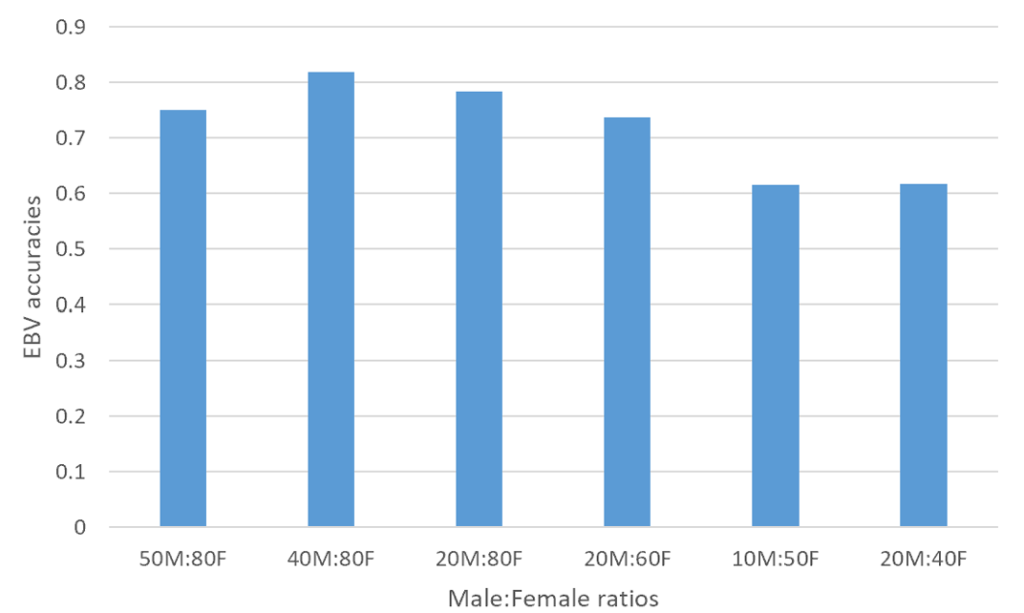

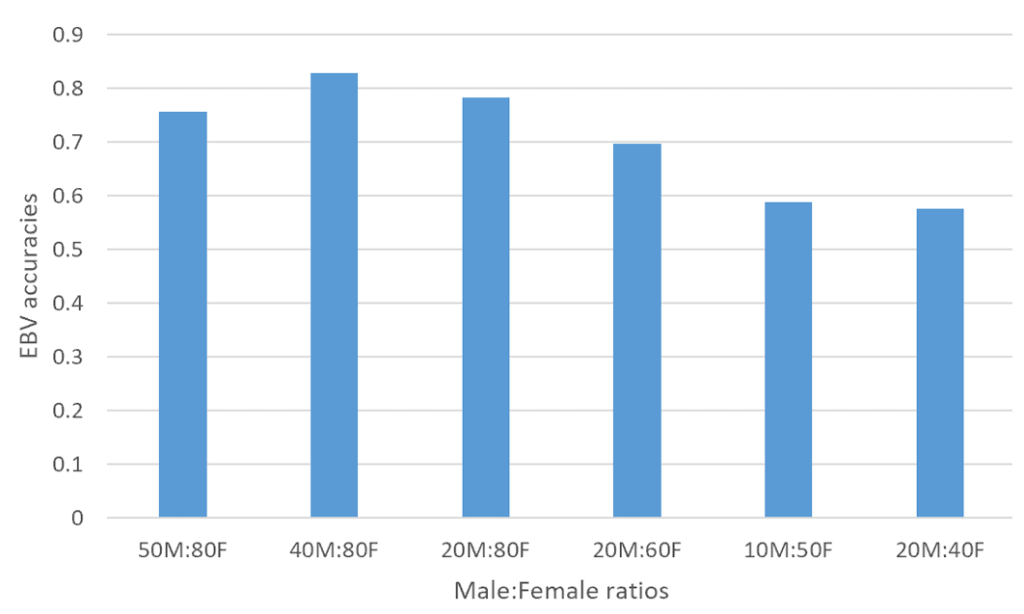

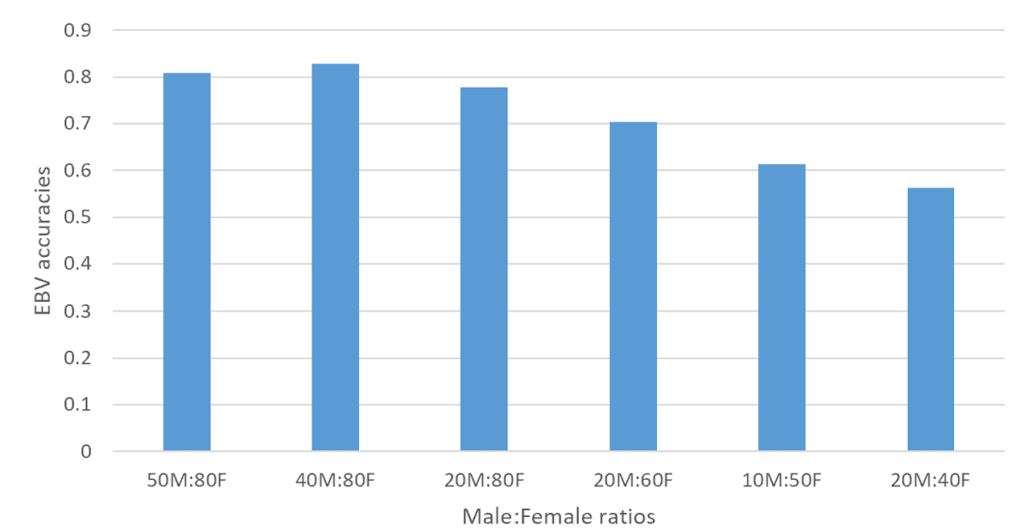

In order to investigate the impact of sex replacement strategies on the accuracy of estimated breeding values (EBVs), a simulation study was conducted using QMSim software to generate data sets. The focus on generations 7–9 was based on the need to evaluate accuracy at a point where genetic equilibrium is likely achieved after initial selection cycles. Earlier generations may still be influenced by founder effects, while later generations may experience diminishing gains due to genetic saturation or inbreeding accumulation. Various scenarios were considered, with male to female ratios ranging from 50M:80F to 20M:40F across different generations (Figure 1, 2, and 3). The key findings reveal that the scenario with 40M:80F consistently yielded higher accuracy of estimated breeding values compared to other strategies across all generations. Conversely, the scenario with 20M:40F exhibited the lowest estimated breeding value accuracy. These results suggest that maintaining a specific balance between male and female ratios can have a significant impact on the accuracy of breeding value estimates. Furthermore, the superior performance of the 40M:80F scenario in terms of estimated breeding value accuracy, compared to other scenarios, may be attributed to a more balanced and diverse representation of genetic material. This balance likely allows for increased genetic variability, which contributes to a more accurate estimation of breeding value accuracy. The ratio of 40M:80F suggests a more balanced distribution of genetic material between sexes. This balance aids in capturing a wider range of genetic variations, thereby enhancing the accuracy of breeding value estimates. This finding aligns with previous research (Hill, 2000), which emphasizes the importance of diverse representation of genetic material for continuous genetic improvement. Additionally, the results suggest that a larger pool of males and females facilitates more effective mating strategies, leading to a better combination of favorable genetic traits and ultimately enhancing the overall genetic quality of the population (Pe´rez-Gonza´lez et al., 2014). The superiority of the 40M:80F scenario can be attributed to the larger number of breeding pairs, which helps mitigate the risk of inbreeding. Inbreeding can have a negative impact on genetic diversity, and by having a higher number of breeding pairs, the likelihood of close relatives mating is reduced.

Figure 1. An illustration of accuracy of EBVs in generation 7 across various sex replacement strategies

Figure 2. An illustration of accuracy of EBVs in generation 8 across various sex replacement strategies

Figure 3. An illustration of accuracy of EBVs in generation 9 across various sex replacement strategies

On the other hand, the 20M:40F scenario, being less favourable could be influenced by limited genetic diversity. A smaller number of breeding pairs may result genetic diversity, making it challenging to capture full range of genetic variations present in the population. With fewer breeding pairs, there is an increased risk of close relatives mating, potentially leading to higher levels of inbreeding and reducing the accuracy of breeding value estimates. The smaller population size in this scenario may create a genetic bottleneck, limiting the variety of genetic material available and impacting the accuracy of breeding value estimates. These factors collectively contribute to the observed differences in the accuracy of estimated breeding values across different sex replacement scenarios. Also, the loss of genetic variation within a breed is related to the rate of inbreeding that is in the absence of selection, inbreeding is related to the number of sires and dams (Cossu et al., 2022; Diffner et al., 2022).

The results of estimated breeding value accuracy across generations indicated superior performance of the 40M:80F scenario across multiple generations (7, 8, and 9) and could be influenced by several factors. Over successive generations, the 40M:80F scenario might have allowed cumulative genetic improvement. The larger pool of breeding pairs facilitates the selection of desirable traits, leading to continuous enhancements in genetic quality. The sustained accuracy across generations suggests that the 40:80M scenario consistently maintains a high level of genetic diversity. This stability in diversity ensures that a broad range of genetic variations is considered, contributing reliable breeding value estimates over time. Also, the scenario’s larger effective population size may help avoid issues related to genetic drift and inbreeding depression over multiple generations (Novo et al., 2022). This stability in population dynamics contributes to continued accuracy of estimated breeding values. Furthermore, the 40M:80F scenario might also, exhibit adaptability to changing environmental or breeding conditions over successive generations. This adaptability can be crucial in maintaining accurate breeding value estimates in dynamic settings. In addition, the larger breeding pool allows for more effective selection strategies over generations (Pe´rez-Gonza´lez et al., 2014). This can include targeted mating to reinforce desirable and avoid detrimental ones, leading to a more refined and accurate estimation of breeding value accuracy. The enduring superiority of the 40M:80F scenario across multiple generations suggests that it not only provides immediate benefits in terms of breeding value accuracy but also demonstrates resilience and consistency in maintaining these benefits over time. On the contrary, the suboptimal performance of 20M:40F scenario indicates potential limitation in genetic diversity and effective mating strategies. This imbalance may have led to reduced accuracy in estimated breeding values across generations, emphasizing the importance of maintaining an adequate number of breeding pairs for optimal outcomes.

However, it is important to acknowledge the study’s limitations. The simulation relied on simplified mating models and computational constraints, which may not fully capture the complexities of real-world breeding programs. Additionally, while the study initially speculated on genetic diversity, a more data-driven approach was adopted by reporting inbreeding coefficients under different replacement scenarios. The results indicate that higher male-to-female ratios (e.g., 40M:80F) may contribute to lower inbreeding levels, thereby preserving genetic diversity and enhancing the accuracy of estimated breeding values. In contrast, the 20M:40F scenario, with its smaller effective population size, exhibited higher inbreeding coefficients, which likely contributed to its reduced accuracy. Although this study primarily examines the impact of replacement strategies on EBV accuracy across different selection intensities, future research could explore how herd size variations influence these dynamics. Incorporating small, mid-sized, and large herd scenarios could provide deeper insights into the scalability of genetic improvement strategies. Though, such an expansion would require significantly greater computational resources and more complex modeling approaches, which were beyond the scope of this study. Regarding genetic diversity, rather than speculating on its effects, we have computed inbreeding coefficients for each replacement scenario. These data support our observation that strategies which maintain a greater number of breeding pairs result in lower inbreeding levels and, consequently, higher EBV accuracy. Future research could further explore these dynamics by incorporating additional genetic markers and broader population parameters. Upcoming studies could integrate these factors to further enhance the applicability of our findings. Also, future research should explore the integration of genomic selection methods to further refine breeding strategies. The use of genomic data could improve selection precision by identifying and leveraging specific genetic markers associated with desirable traits. Additionally, investigating long-term genetic trends under different sex replacement strategies would provide deeper insights into the sustainability of various breeding programs.

In many developed countries, artificial insemination (AI) has become the predominant breeding method for beef production, with reliance on a limited number of highly proven sires of very high EBV accuracy. This strategy accelerates genetic progress but may reduce genetic diversity because of dependence on only a few elite bulls. By contrast, in developing countries such as Nigeria, natural mating remains the major breeding system, making sex replacement strategies highly relevant. Therefore, the insights from this study are particularly applicable in developing-country contexts, while also providing complementary perspectives for AI-based systems regarding the trade-off between EBV accuracy and genetic diversity.

In summary, our simulation study emphasizes the critical significance of sex replacement strategies in influencing the accuracy of estimated breeding values. The scenario with 40M:80F emerged as the most effective, providing valuable insights for livestock breeding programs seeking to enhance genetic improvement. These findings contribute to the ongoing discourse on optimizing breeding practices and highlight the need for a nuanced approach to sex replacement strategies in livestock populations. Moreover, while artificial insemination with elite sires is common in developed countries, where EBV accuracy is often maximized, natural mating remains the dominant practice in many developing countries such as Nigeria. Therefore, the insights generated here are especially relevant for production systems where AI uptake is limited, while also offering complementary perspectives for AI-driven systems on balancing EBV accuracy with genetic diversity.

This study was carried out with the support of the African-German Network of Excellence in Science (AGNES) Junior Researcher.

The authors certified that there is no conflict of interest with any financial organization regarding the material discussed in the manuscript.